Did you ever receive one of those 90s chain emails in your inbox? You know, the kind where you fill in your favorite band/animal/team/color/etc. and then send it to ten friends or else you’d have bad luck for the week?

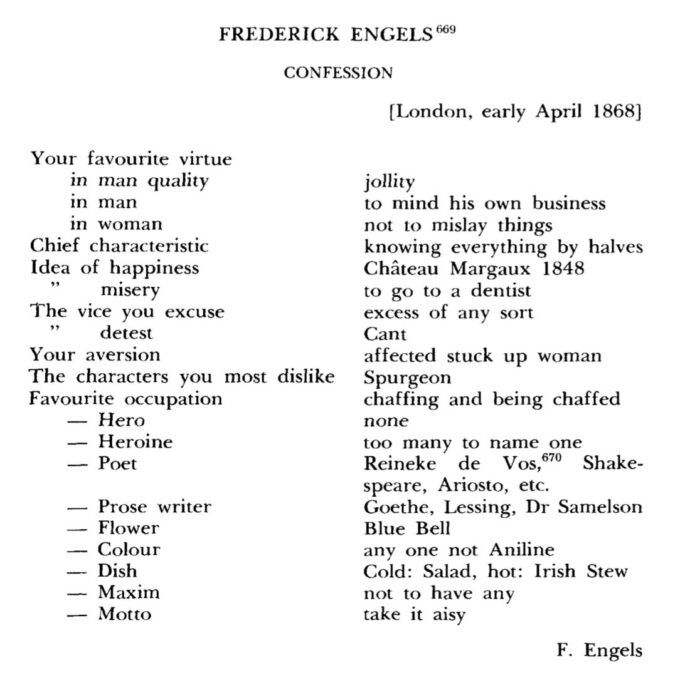

I recently stumbled across a 19th century version, a “confession” filled out by Friedrich Engels, the original champagne socialist who is now best known for popularizing Karl Marx’s ideas.

Little on the list is truly surprising. Engels wouldn’t be the first notorious womanizer (and accused rapist) to declare his love for women even while evincing a base misogyny.

But the answer that immediately caught my eye was Engels’ favorite color: “Any one not Aniline.” Now, if you’re an ordinary, well-adjusted denizen of the 21st century, odds are that you immediately considered opening a new tab to ask Google, “What color is aniline?”

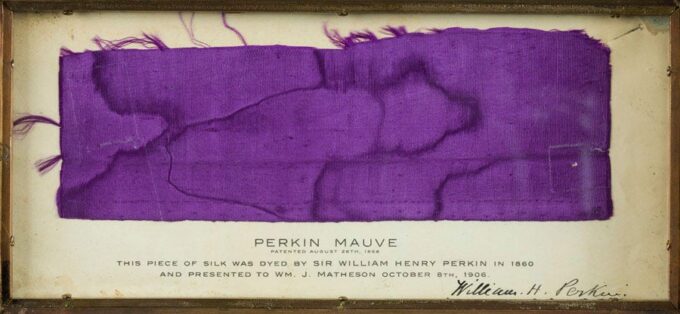

There’s no need to click away. Aniline was mauve. And it is hard to overstate the extent to which various shades of the new purple swept the world of fashion in the 1850s and 1860s.

That’s because aniline was the first commercially-scalable synthetic dye, invented at a time when chemists were unlocking the secrets of the universe by distilling, vaporizing, and generally futzing with every substance they could get their hands on.

Aniline was actually the product of a failed British attempt in 1856 to synthesize quinine in hopes of making anti-malarial treatments cheaper and easier to produce than the old way of grinding up the bark of a hard to acquire Amazonian tree. The result wouldn’t especially help imperialists expand their empires over mosquito-infested jungles, but it did produce a particularly vivid shade of purple.

The researcher, an eighteen year old college student named William Perkin, was also an amateur painter, and immediately saw the value of a cheap, easy to produce dye that was more durable than existing alternatives. Seeking capital investment, Perkin partnered with Robert Pullar, a Scottish dye entrepreneur who would later become a radical pro-free trade member of Parliament. By the end of the century, Perkin and Pullar owned a global network of synthetic dye factories that brought color to the masses.

This meant that purplish, pinkish, and reddish dyes were suddenly this cheap and widely available for the first time in human history. Tweaking the distillation process could produce mauveine, fuchsin, and safranin, which are the synthetic forerunners of the colors we call mauve, fuchsia/magenta, and saffron today. It may have been the single most significant moment in modern fashion history.

Prior to this, many of the dyes used for clothing and paint had to be ground up from natural ingredients. For instance, if you lived in 4th century Rome and wanted to wear purple clothing, you needed someone to find and grind up twelve thousand snails of a particular species that lived mostly in the Eastern Mediterranean Sea. Doing so would yield 1.4 grams of dye, which was barely enough to color the trim of a single piece of clothing. The cost of purple was thus astronomical; pound for pound, “Tyrian purple” was worth three times as much as pure gold! And purple dye was so hard to acquire, at any price, that sumptuary laws often prohibited anyone except royalty from wearing purple clothing.

But after 1856, the ability to synthesize aniline meant that purple hues were suddenly everywhere. What had once cost pounds of gold now cost mere pennies. Mauve was all the rage — people were contracting “mauve measles,” as British wags put it — a fact that would not have been lost on Engels’ when he wrote out his list in 1868 since his family fortune was tied up in textiles. (He properly capitalized “Aniline” since it was then still a proprietary product.)

When you see televised depictions of Victorian era fashion, like middle class women wearing acres of brightly-colored fabric, you are looking at a byproduct of the synthetic dyes revolution.

And that wave of color cascaded step-by-step, class-by-class, down throughout society. Cheaper, more durable, and more vivid products abounded, from housepaints to wallpapers. Today, we take for granted the idea that color is near costless. It would strike a 21st century consumer as bizarre if they were told that a bright purple dress or mauve house paint would cost 10x (or 1000x) the price of one that was white.

Even so, the rise of synthetic purple sparked a sartorial reaction. Purple, as long as it was rare and inaccessible to the plebeians, was considered dignified, elegant, and noble. But once purple became commonplace, it was gauche and uncouth. A century later when cultural critic Paul Fussell summarized the ways that dress signified class status, he lumped purple in with polyester fibers and sports jerseys as markers of belonging to the grubby “proles.”

And that brings us back to Engels’ sneering response, “Any one but Aniline.” On the one hand, it’s not surprising that a textile manufacturer might be annoyed at the disruption to his existing (and profitable) supply chain. Engels was also a product of inherited wealth, and making fun of Aniline was common sport for his class at the time. A satirical Punch cartoon of 1877 featured a dilettante sniveling about a debutante, “She affects Aniline dyes, don’t you know! I weally couldn’t go down to suppah with a young Lady who wears Mauve twimmings in her skirt, and magenta wibbons in her hair!”

Pecuniary self-interest and class snobbery aside, Engels wouldn’t be the first socialist guilty of reflexive suspicion towards technological innovation and the capitalists that had made it possible. The Luddites you will always have with you.

For whatever reason, Engels failed to see how the invention of synthetic dyes was a boon to workers and society as a whole, a future in which the rare colors of kings would become the ordinaries of proles. Capitalist incentives had once again commissioned a technological innovation that could push back against harsh, natural scarcity. Life would become a little bit brighter and bolder because of it.

Every one Aniline.

This article was published at Matzko Minute on 8/28/2023.