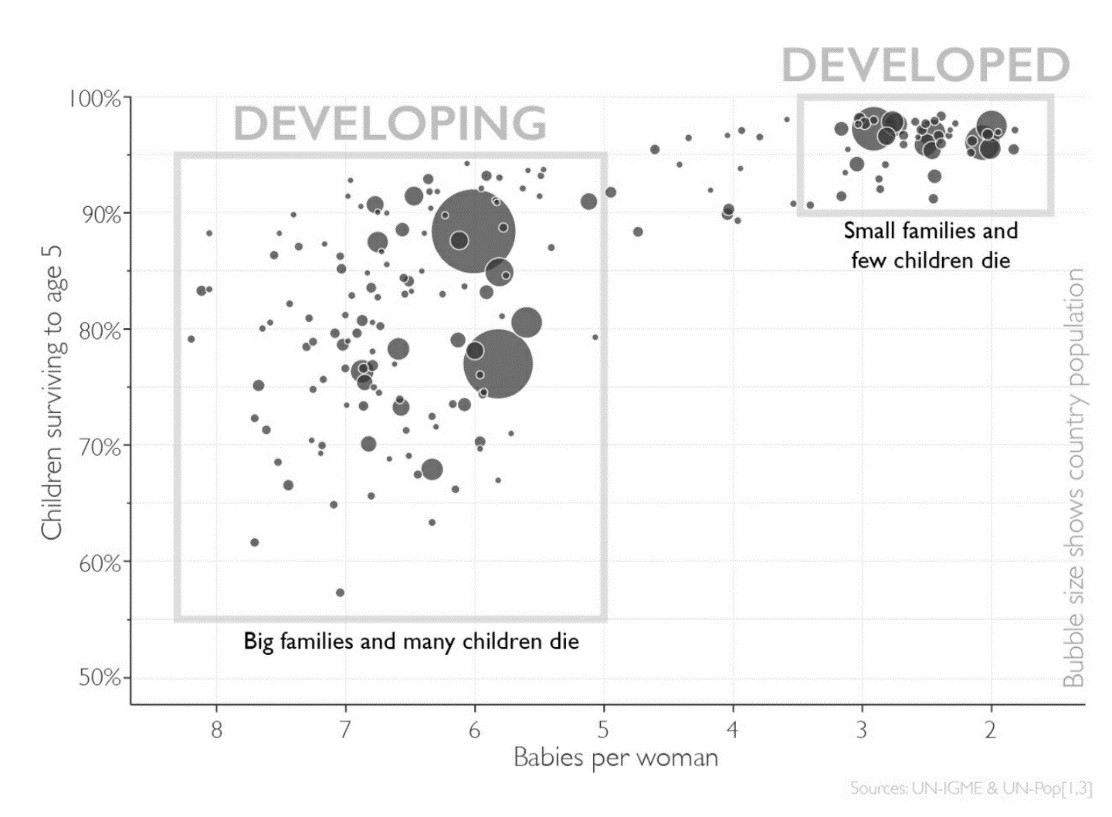

In the book he published shortly before his death, the late professor of global health, Hans Rosling, recounted a story of interacting with his students. Used to thinking about countries in terms of “rich” and “poor”, “developed” and “developing” or “West” and “the rest”, Rosling’s students struggled with accounting for some rapidly improving countries in Latin America and Southeast Asia. Ok, Rosling acquiesced, and displayed one of his iconic bubble graphs with rates of children surviving to age 5 on the y-axis and average number of children per woman on the x-axis:

Around the neatly clustered countries, Rosling drew two boxes aligning with the smug students’ inclinations, humming with confirmation bias satisfaction: a clear divide between developed countries where women have few children, few of whom die, and developing countries where women have lots of children, but many of them die.

“What’s wrong with this picture?” Rosling asked. Well, that’s what the world looked like in 1965 – not today.

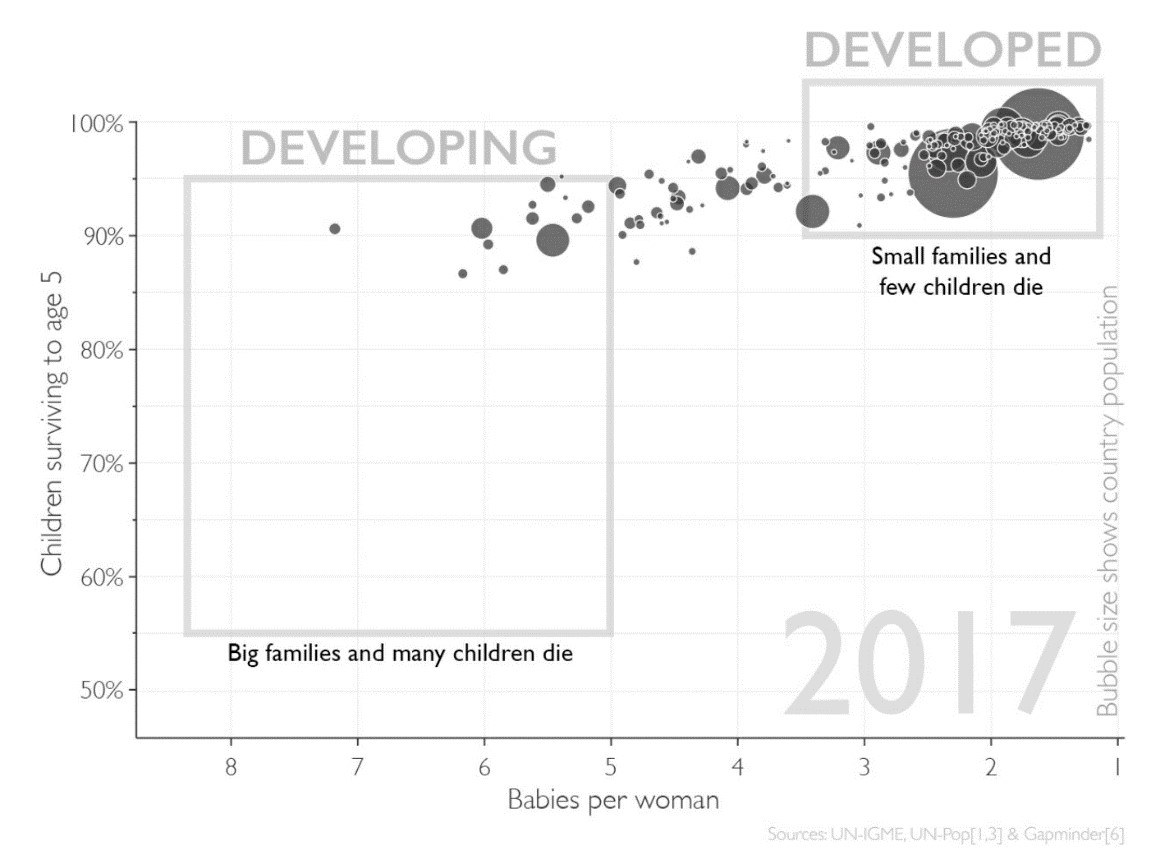

Their mental framework, what they believed the state of the world to be, was decades old! Outdated. And it wasn’t limited to youthfully ignorant university students. Wherever Rosling ran his famous Gapminder tests, most respondents got few – if any – questions right. Teachers, journalists, politicians and Nobel Laureates were way too pessimistic, scoring “worse than chimpanzees” on multiple choice questions of undisputed data.

Today, every single country has seen those two metrics improve and most women in most countries have between one and three children – the global average is less than 2.5:

Across the board, in almost every way we can measure it, life is becoming better everywhere. Not for everyone in every single year or on every single metric – that wouldn’t be progress, Steven Pinker points out, but a miracle – but over time progress seems all but guaranteed. This shouldn’t come as a surprise to a well-informed observer; sites like HumanProgress or OurWorldInData.org are filled with metrics capturing our species’ tireless progress. Best-selling books by Steven Pinker, Johan Norberg, Bjørn Lomborg, Matt Ridley and writers like Marian Tupy and Alexander Hammond diligently spread this enlightened message. “Reality,” writes economist Bryan Caplan, “has a well-known libertarian bias.” Markets work, and technology and capitalism are making us better off.

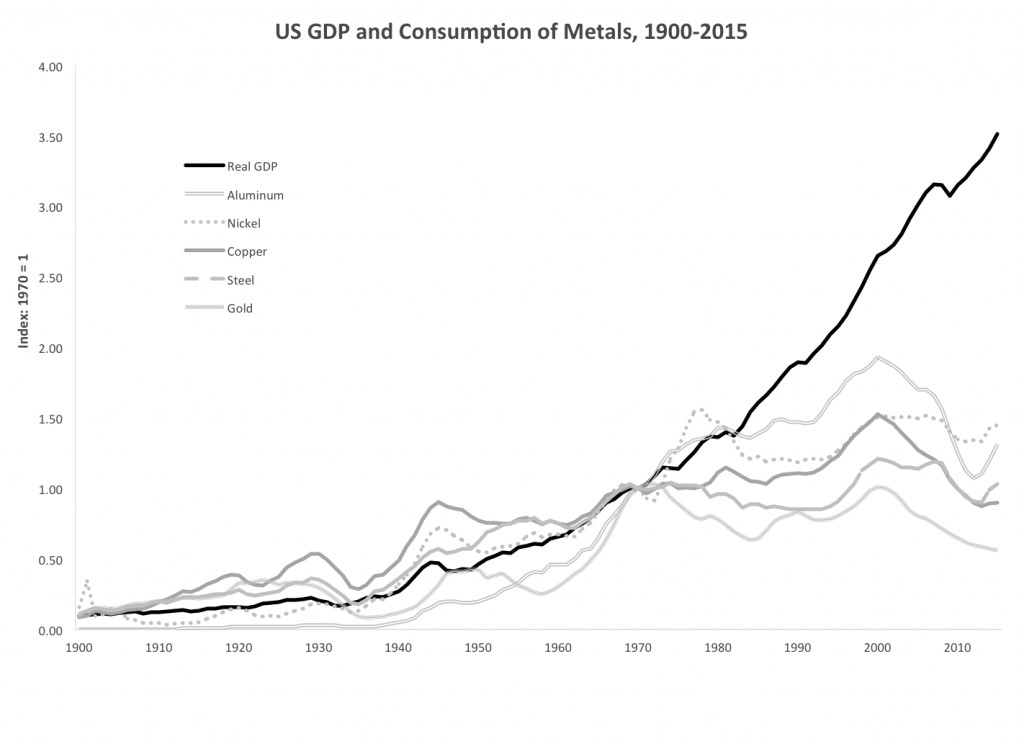

What may come as a surprise is another profoundly outdated worldview. Most of us walk around with the implicit assumption that more and higher economic growth requires more material inputs. To fuel our growing economies and populations, we need to extract more raw materials from the ground, chop down more forests and burn more coal; our ecological footprint grows in tandem with our economic consumption. After all, that’s what the teenage angst and calls for various radical upheavals are ostensibly about.

A fascinating new book, More From Less, by MIT technology scholar Andrew McAfee (who is also the latest addition to HumanProgress’s board) suggests that this too is an outdated view. Indeed, the great decoupling of resource use from economic growth has been well-known by environmental economists for decades, but has failed to become common knowledge. McAfee shows that the total use of raw materials tracked by the U.S. Geological Survey have stagnated or declined over the last 20-30 years, even while GDP and population have kept growing.

Economic growth is no longer “something that depends on always feeding more of nature’s resources into the hungry maw of industrialization,” writes Noah Smith in discussing McAfee’s book. Through technological improvements and capitalist competition, we’re simply getting more “economy” from less stuff.

This trend has been observed in other countries too, for instance the UK – the country that has reduced its emissions more than other EU countries (most of all if we exclude a handful of formerly Soviet-dominated countries). Chris Goodall’s “Material Flow Accounts” show that Britain’s use of raw materials peaked sometime in the mid-2000s, a finding that predictably enraged George Monbiot but has otherwise been mostly ignored.

Not only are most apocalyptic claims we’ve grown accustomed to not true, the reality is that things are getting better. Every major Western country sees its emissions falling and when rapidly-growing poor countries get rich enough to have their basic needs satisfied, they too will follow. The sky is only falling if you listen to the activists; the stats and the scientists are telling us that most high-income countries have already turned it around.

The decoupling of energy and raw materials from GDP growth is not seen by scholars as an automatic process. McAfee’s new book carries the same message: we need to do more of what we’re already doing: capitalism, technology, public awareness and smart (rather than invasive) regulation. Progress means that things are getting better – even in the areas our friends and family worry about the most.

Hans Rosling’s legacy to the world was his tireless desire to change our pessimistic views on the state of the world. He did it for many common health metrics like child mortality, income and population growth, but it holds equally well for resource use.

Our views on the state of the world are decades behind. We need an update and an infusion of data-rich realism.