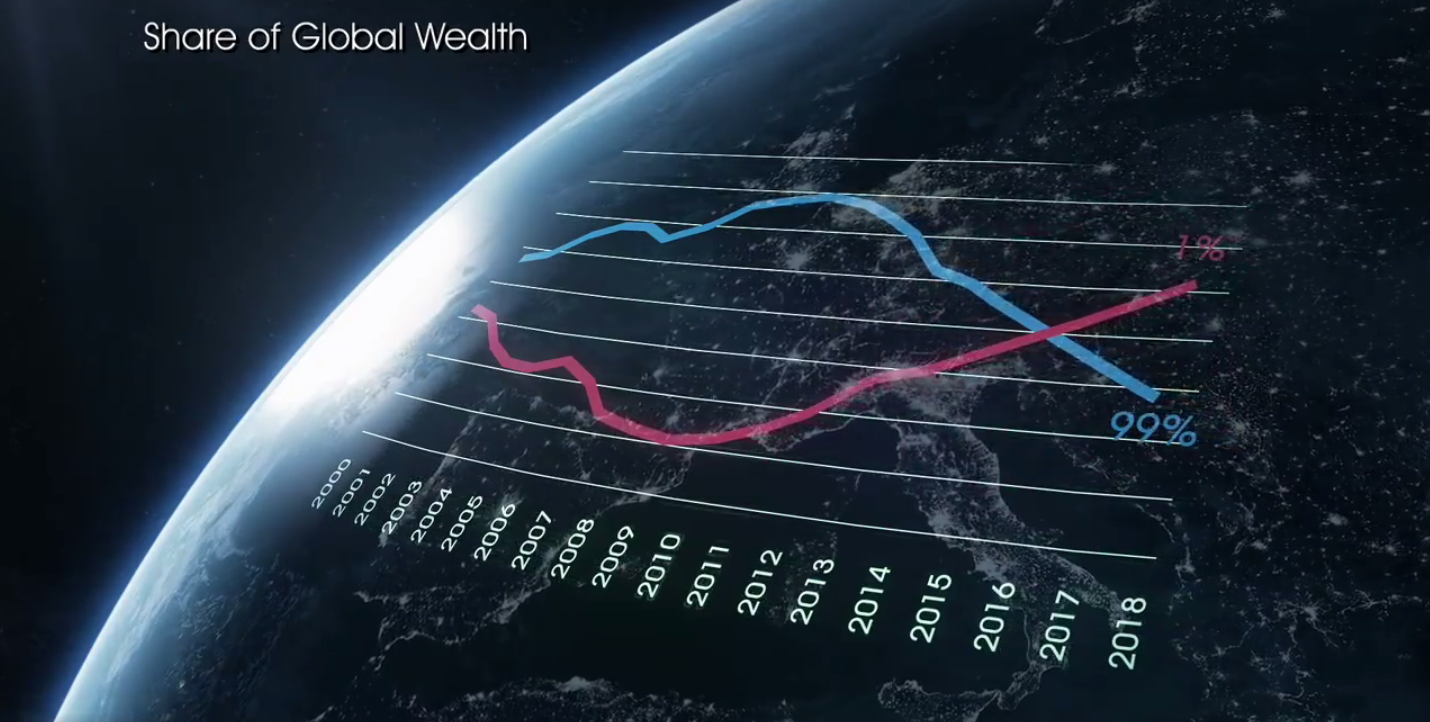

This past weekend, The Economist uploaded and shared a short video to its Facebook page called, “The year of the 1 percent.” The video shows a graph superimposed over the Earth seen from space, while a voice narrates, “2016 is set to be a more unequal world than ever before. For the first time, the richest 1 percent of the population will enjoy a greater share of global wealth than the other 99 percent.” The video has been viewed more than one hundred thousand times.

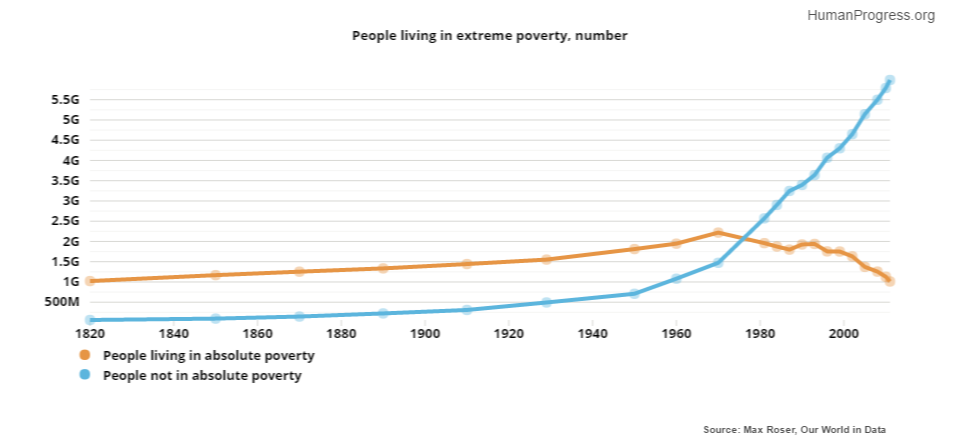

The Economist’s graph reminded me of another graph, which also shows two lines that eventually cross but tells a very different story. Despite population growth, there are fewer people living in extreme poverty today than ever before:

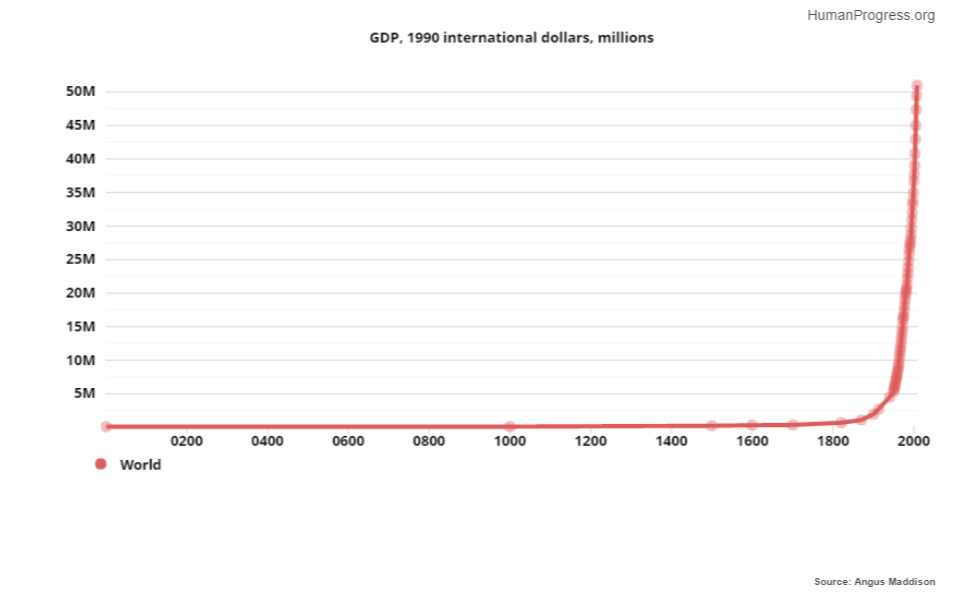

How can both graphs be accurate? Poverty can decline even as inequality rises, as long as the total amount of wealth in the world is growing. To ignore this is to fall prey to the “fixed pie fallacy.” Throughout most of human history, global wealth hardly changed. But thanks to trade and industrialization, wealth has skyrocketed since the 1900s and continues to climb. At the same time, technological advances have also increased human wellbeing in ways not captured by looking at GDP alone.

Because the pie is growing, focusing solely on inequality, like The Economist’s video did, makes little sense. Most of us would rather have a relatively small slice of a gigantic pie than the biggest slice of a microscopic pie. In other words, most of us would rather be wealthier in absolute terms, regardless of our relative position. This is why many of us, if given the choice, would choose to be an ordinary person today instead of a member of the upper crust a century ago or a 17th century king.

This first appeared in Cato at Liberty.